The RMA replacement has arrived.

Since its election in 2023, the Government has remained committed to a full overhaul of New Zealand’s resource management system. Over the past three years, changes have been made in three phases, starting with the repeal of the previous Government’s Natural and Built Environment and Spatial Planning Acts, followed by several amendments to the Resource Management Act 1991.

Now, the most significant stage of the reform has arrived: two new Bills intended to replace the RMA have been introduced to Parliament. The Planning Bill regulates how land can be used and developed, and the Natural Environment Bill regulates the management and use of natural resources and the protection of the environment.

In announcing the Bills today, Minister Bishop and Under-Secretary Court say that the new system “will make it easier to build the homes and infrastructure our country needs, give farmers and growers the freedom to get on with producing world-class food and fibre, and strengthen our primary sector while protecting the environment”.

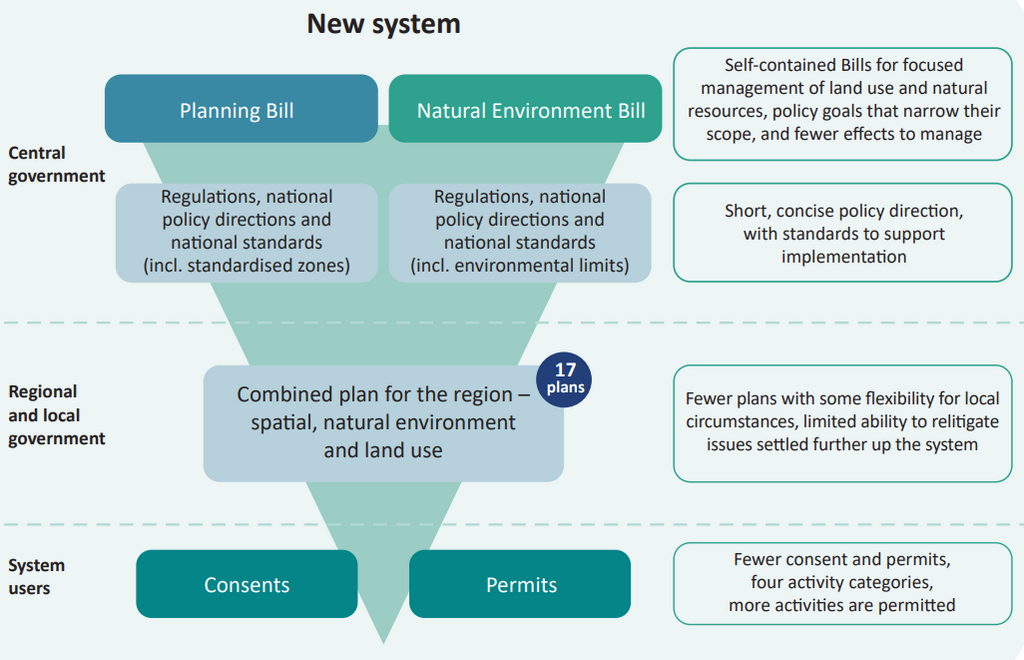

The new dual scheme adopts a funnel approach, making the system highly directive at the top. As the process moves downward, like an inverted pyramid, it becomes progressively narrower, and the scope of what can be regulated becomes more limited. This goal is to require fewer resource consents for different activities once the bills become law.

The Planning Bill and the Natural Environment Bill will both require their own set of national policy directions, outlining the goals of the legislation (and how any conflicts in the ‘goals’ of the Planning Bill and Natural Environment Bill will be resolved) and the Government’s expectations of local authorities and system participants. National standards will then provide detailed guidance and technical specifications to support the development of new plans and inform decision-making. The Government proposes to deliver these national instruments in two stages, one tranche by the end of 2026, and another in mid-2027.

As signalled, at the local government level, national direction will shape the development of combined regional plans. Each plan will include a spatial component and a natural environment and land-use component. In total, the intention is that there will be only 17 combined regional plans across the country (compared with over 100 currently).

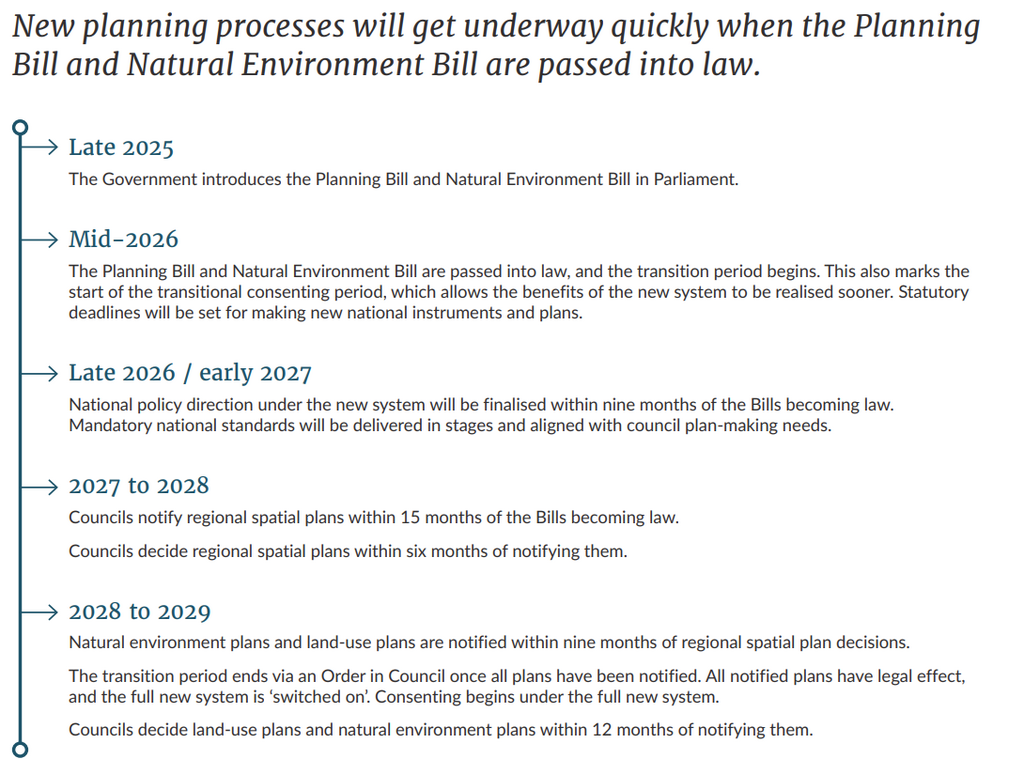

With the introduction of the two Bills today, the first reading in Parliament is likely to be next week. This means the submission period on the Bills will fall in early 2026 (to be confirmed when the Bills are sent to the Environment Select Committee). The Government aims to pass the new legislation by mid-2026 (prior to the next election).

The Government has ambitiously signalled it intends the new system to be fully operational by 2029, with local authorities being required to develop combined regional plans by then. A transitional consenting framework will be in place until the system is fully operational. The key transitional arrangements are:

- Urgent legislation: Introduction of the Resource Management (Duration of Consents) Amendment Bill to extend existing consents that would otherwise expire, until 31 December 2027 (with some exceptions).

- Further extensions: The new Planning Bill and Natural Environment Bill will provide for additional extensions, likely until around 2031.

- Transitional consenting process: New consent applications can still be made during the transition. These will follow a modified RMA process with limits on public notification and the scope of effects considered, immediate introduction of core national standards, creating consent-free pathways for certain activities, and procedural principles such as proportionality to streamline decision-making.

At a more specific level, some of the notable changes in the new Bills include:

- The removal of certain effects from the scope of consideration during the resource consenting process, including internal and external layout of buildings, visual amenity, views from private property and precedent setting effects.

- Removal of non-complying and controlled activities, creating a generally more permissive framework with fewer consent requirements.

- Participation in the consenting process being restricted to those who are materially affected, and a higher threshold for notification focused on adverse effects that are more than minor (under the Planning Bill) and significant (under the Natural Environment Bill). Public notification will only occur where such effects exist and not all affected parties can be identified.

- Additional restrictions have been placed on the consideration of ‘effects’, which specify that ‘less than minor adverse effects’ must not be considered by decision-makers. The provisions do attempt to refer to cumulative effects, but given the changes in definitions, and the fact that the RMA has struggled to effectively control cumulative effects – this amendment is likely to be controversial.

- A new regulatory relief framework that will require councils to provide relief to landowners where planning controls (such as outstanding natural landscapes, significant historic heritage and sites of significance to Māori) have an unreasonable impact on their land. This is expected to be a controversial part of the new regime, particularly given the recent ‘rates cap’ announcements.

- The establishment of a new Planning Tribunal to resolve lower-level disputes (including requests for further information, notification decisions and interpreting consent conditions), with the Environment Court remaining for appeals (including relating to proposed plans, notified consents, designations, enforcement order applications and points of law appeals from the Planning Tribunal on some matters). The Planning Tribunal will be a division of the Environment Court, with its own chairperson and pool of adjudicators. The ability for the Environment Court to consider direct referrals and nationally significant proposals is to be removed from the system.

- The removal of the existing provisions relating to cultural matters, previously outlined in s6(e), 7(a) and 8 RMA and its replacement with a descriptive Treaty of Waitangi clause outlining how the Crown’s responsibilities under the Treaty are met, including requirements to consult iwi authorities and customary marine title groups during the preparation of national instruments, regional spatial plans, and land use plans, and to have regard to relevant iwi planning documents and statutory acknowledgements.

Watch this space for our useful further guidance on the detail of the new legislation. Alongside the introduction of the Bills, the Ministry for the Environment has also released fact sheets explaining what these changes mean for indigenous biodiversity and the environment, homeowners, residential developers, the infrastructure sector, Māori interests, the farming sector, and the marine sector.

If you would like advice on what the changes mean for you, or if you would like assistance drafting submissions on the Bills through the Select Committee process (closing date for submissions 13 February 2026), please contact a member of our Local Government, Resource Management and Regulatory team.

The images included in this article were sourced from ‘Better planning for a better New Zealand – Overview of New Zealand’s new planning system’ by the Ministry for the Environment and can be found here