Adapting to a changing climate in NZ

Topics covered in this article: Sustainability & Climate Change

Special Counsel

Phone: +64 7 927 0522

Email: rzame@clmlaw.co.nz

Bachelor of Laws, Bachelor of Science, University of Otago

Last week saw the release of NZ’s first National Adaptation Plan. Our previous article looked at the draft Adaptation Plan released by Government in April 2022[1]. In this article we consider the final version of the Plan and the issues that are yet to be addressed.

What does the National Adaptation Plan cover?

As explained in our previous article, the National Adaptation Plan sits alongside the Emissions Reduction Plan and together they are intended to lay out New Zealand’s overall response to climate change and enable a transition to a low-emissions, climate-resilient future.

The National Adaptation Plan[2] recognises that some of the climate impacts are already locked in and accordingly adaptation is required. The Plan focuses on addressing 43 priority risks New Zealand faces from the impact of climate change from 2020-2026, as set out in the National Climate Change Risk Assessment 2020.

The first Adaptation Plan covers the period 2022-2028. The intention is that National Climate Change Risk Assessments (and correspondingly the National Adaptation Plan) will be updated every six years, to account for the changing climate and associated risks. The 2nd National Climate Change Risk Assessment will be undertaken in 2026, with a new National Adaptation Plan due in 2028.

The Climate Change Commission is required to prepare two-yearly progress reports on the effectiveness of the Plan in reducing risks, with the Government required to respond to the Commission’s reports within 6 months.

From 30 November 2022 regional councils, when preparing regional policy statements and regional plans, and district councils when preparing district plans, will be required to have regard to both the Emissions Reduction Plan and the National Adaptation Plan.

What are the focus areas and critical actions identified in the Plan?

The draft Plan contained three focus areas, which have now been incorporated into four priorities:

- enabling better risk-informed decisions;

- driving climate-resilient development in the right places;

- laying the foundations for a range of adaptation options including managed retreat; and

- embedding climate resilience across government policy.

The Plan continues to provide for actions relating to six areas:

- System-wide issues (SW); and

-

The following five ‘outcome areas’ which broadly align with those identified in the risk assessment:

- Natural environment;

- Homes, building and places;

- Infrastructure;

- Communities; and

- Economy and financial system.

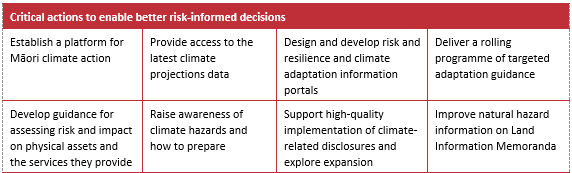

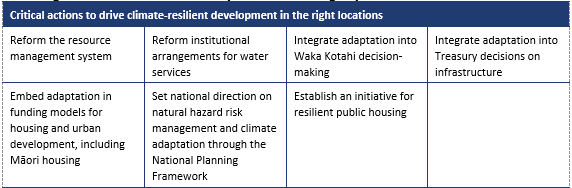

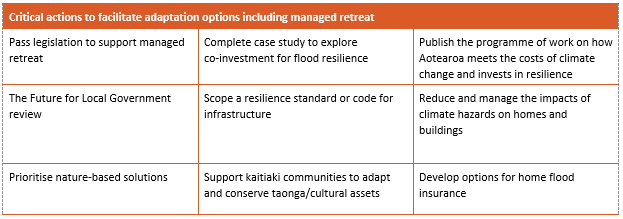

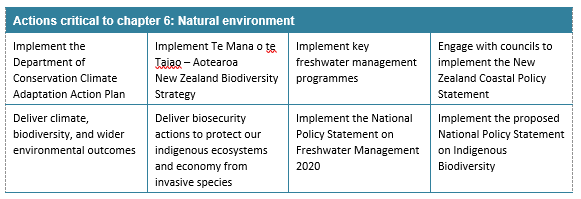

Actions are identified in the Plan as critical, supporting or proposed. The Plan sets out the following critical actions under each of the four ‘priority’ areas. The ‘critical actions’ are largely unchanged from the draft version of the Plan, but have been reordered into the four priority areas. Summary tables of the ‘critical actions’ from the Plan are set out below:

Enabling better risk-informed decisions

Driving climate-resilient development in the right places

As outlined in our earlier articles, significant reform of the resource management system in New Zealand is currently underway. As highlighted under the Adaptation Plan, councils face significant pressure to enable further development to meet housing requirements; and often significant resistance from developers and landowners when promulgating plans which address natural hazard risks. Councils, through their submissions on the draft Plan, asked central government to provide stronger mandates for assessing and managing climate risk, particularly during the transition period into the new resource management system.

However, most of the items listed in response relate more directly to upcoming reform (for example, reform of the resource management system (Action 4.1), setting national direction through the proposed National Planning Framework (NPF) (Action 4.2) and reform of water services (Action 4.5). During the transitional period, councils are advised to use recommended climate change scenarios as set out in the Adaptation Plan when making or changing regional policy statements or plans (required from November 2022) and to ‘stress test’ plans, policies and strategies using a range of scenarios as recommended in the interim guidance and the National Climate Change Risk Assessment Framework[3].

Councils are also directed to improve natural hazard information on LIMs (Action 3.6) and provide access to projections data (Action 3.1). However, legislative changes are identified as being required to the Local Government Official Information and Meetings Act 1987 (LGOIMA) to provide for improved natural hazard disclosure on LIMs, and that is proposed to occur by the end of 2023. Action 3.1 relates to a NIWA Projections Project to make global climate projections from the most recent IPACC report more applicable to New Zealand and datasets are expected to be produced by January 2023.

Laying the Foundations for a Range of Adaptation Options including Managed Retreat

Another significant aspect of the Adaptation Plan is the facilitation of adaptation options, including managed retreat.

The Plan indicates that 675,000 (or one in seven) people in NZ live in areas prone to flooding, which equates to nearly $100 billion worth of residential buildings. A further 72,065 people live in areas projected to be subject to extreme sea-level rise. The number exposed will increase as climate changes.

The Adaptation Plan indicates that, where risks occur in existing places, councils and communities should consider the full range of adaptation options[4], which could include:

- Avoiding risk – for example by locating development away from areas prone to hazards;

- Protecting assets from risk – for example, by building protective structures such as sea walls;

- Accommodating risk – for example by incorporating adaptation options into the design of developments;

- Retreating from risk – for example, by relocating existing development away from high-risk areas.

The last option is often referred to as ‘managed retreat’, which is the purposeful and co-ordinated movement of people and assets away from risks. As covered in our earlier article, the Ministry separately consulted on issues relating to the early development of a managed retreat and flood insurance system. Managed retreat at Matata (following an extreme weather event which caused significant damage) has been complex; and highlighted the need for a national framework on managed retreat.

Such issues are complex, and involve consideration of how risks and costs associated with adaptation should be shared, what a managed retreat process should look like, whether people should be allowed to stay in areas when community services are withdrawn; as well as issues of equity, flood insurance, and managed retreat when climate change affects Māori coastal and river settlements.

Many of these issues remain unanswered by the Adaptation Plan. It indicates that a hybrid approach using different adaptation options may be appropriate, and that the options used may change over time. It also indicates that councils should work with communities to assess options that will be adopted, but leaves key issues for future processes including further central government direction (including through RMA reform and local government review), the legislative mechanics of managed retreat (if required) and, more importantly, how such matters will be funded.

The Natural and Built Environment Act (NBEA) and Spatial Planning Act (SPA), which will replace the RMA, are expected to be introduced to Parliament by the end of the year. A separate piece of legislation, the Climate Adaptation Bill, which will address the technical, legal and financial issues associated with managed retreat, is expected to be introduced by the end of 2023. Local government review is also underway and is expected to include recommendations on funding and financing, including when central government co-funding might be appropriate for large challenges or shocks, and for local services with national benefits. The final report and recommendations from the Local Government Review Panel is due mid-2023, after which central Government will decide how to respond to the recommendations.

Embedding Climate Resilience Across Government Policy

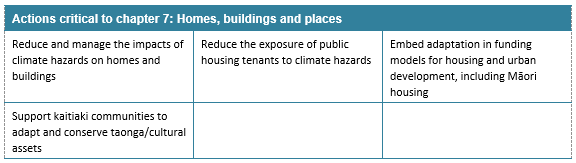

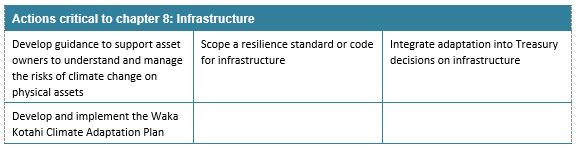

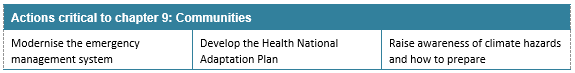

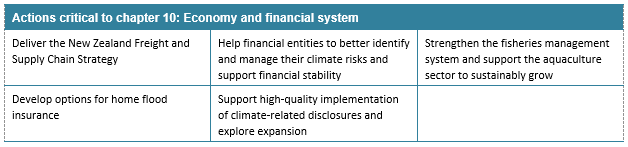

The Plan states that a priority is to embed climate resilience across all government strategies and policies. In terms of the five ‘outcome areas’ it provides the following critical actions:

Natural Environment

Homes, Buildings and Places

Infrastructure

This section focuses on infrastructure such as energy, telecommunications, transport, 3 Waters, waste and social infrastructure (schools, health facilities, community assets, courts, social housing etc). The purpose is to reduce the vulnerability of assets exposed to climate change, ensure all new infrastructure is fit for a changing climate, and use renewal programmes to improve adaptive capacity. This includes developing guidance to support asset owners understand and manage risks to physical assets and the services they provide; scoping for a resilience standard or code for infrastructure; and integrating adaptation into Treasury decisions on infrastructure.

Communities

Economy and Financial System

The Adaptation Plan states that between 2007-2017, contribution of climate change to floods and drought alone cost $840 million in insured damages and economic losses[5]. In 2021 less than 10% of businesses had assessed the risk from a changing climate and less than 20% intended to take action to reduce their risks over the next 5 years[6].

The Plan also highlights that land-based primary industries, fisheries and aquaculture, are the most exposed industries as they depend on climate-sensitive natural resources; and failure to adapt adequately will reduce productivity and potentially viability. Impacts on regional economies and on iwi and Māori reliant on these exposed industries are also identified[7].

It also highlights issues relating to insurance retreat, disrupted supply chains, reduced financial stability and the fiscal impacts of extreme weather and sea-level rise. Actions proposed include a new national Freight and Supply Chain Strategy to address resilience in the supply chain; changes to the Fisheries Act to provide more agile and streamlined decision making in response to fish stock abundance due to the effects of climate change; an Aquaculture Strategy to support industry to adapt to climate change; consideration of whether to extend mandatory climate-related disclosure requirements to public entities; and the Reserve Bank integrating climate change considerations into its supervisory, stress testing and policy work. It also includes work by the Earthquake Commission to develop options for home flood insurance issues.

Conclusions

The Adaptation Plan provides comprehensive coverage of the range of issues that will eventuate with climate change; with many of the critical actions identified already underway. However, key questions and guidance on critical areas including central government guidance for local authorities, the legislative form and funding of managed retreat and other adaptation options are yet to be fleshed out through further legislation and guidance, including upcoming resource management reform.

If you would like further information on any of the issues raised in this article and how it might affect your business, please contact our resource management team.

Latest Update: 10 August 2022

[2] A copy of the Adaptation Plan and information sheets on a range of topics can be found here: https://environment.govt.nz/what-government-is-doing/areas-of-work/climate-change/adapting-to-climate-change/national-adaptation-plan/

[3] Adaptation Plan, p68-69

[4] Adaptation Plan, p79

[5] Adaptation Plan, p154

[6] Ibid, p155

[7] Ibid, p157.