Making moves on managed retreat

Topics covered in this article: RMA, RMA & Local Government, Sustainability & Climate Change

Special Counsel

Phone: +64 7 927 0522

Email: rzame@clmlaw.co.nz

Bachelor of Laws, Bachelor of Science, University of Otago

Civilisation exists by geological consent, subject to change without notice – Will Durrant.

The Environmental Defence Society (EDS) has released its first working paper considering options for the shape of future managed retreat law. The release of the paper is timely given the national civil defence emergency arising from Cyclone Gabrielle and the January 2023 weather events; both of which caused widespread destruction and loss of lives, particularly in coastal and riverside communities. The impact of those devastating events, and the reality that New Zealand will increasingly face risks associated with climate change, has reignited public awareness and discussion about how we manage the ongoing risk to people, properties, assets and critical infrastructure.

The purpose of the EDS paper is to develop recommendations for the content of the new Climate Adaptation Act (CA Act), with a Bill expected to be introduced into Parliament by the end of 2023. As stated in the First EDS paper, the CA Act is intended to address the complex and distinctive issues associated with managed retreat such as funding, compensation, land acquisition, liability and insurance. It is considered necessary because other proposed legislation, such as the Natural and Built Environment Bill and Spatial Planning Bill (currently before the Environment Select Committee), and the existing Public Works Act, are inadequately tooled to enable people and infrastructure to be moved out of harm’s way.

EDS have signalled their intention to release two further working papers – with Working Paper 2 focusing on describing and evaluating the adequacy of current law, administrative arrangements and the rights-based system applicable to managed retreat. Working Paper 3 will present a series of options for incorporation into the new bill to address gaps in the current system. The final synthesis report from EDS, expected in December 2023, will contain concrete recommendations for the design of the CA Act.

The working paper seeks constructive feedback on:

- what the purpose of managed retreat should be;

- what principles should underline it; and

- to what extent funding support should be provided to those affected.

How does this fit with the National Adaptation Plan?

As outlined in our earlier article[1], NZ’s first National Adaptation Plan (NAP) was released in August 2022. That document recognises climate impacts which are already locked in, and focuses on addressing the 43 priority risks New Zealand faces from the impact of climate change from 2020-2026 (as set out in the National Climate Change Risk Assessment 2020). The intention is that both the National Climate Change Risk Assessments, and the NAP, will be updated every six years to account for the changing climate and associated risks. The first NAP covers the period 2022-2028. The 2nd National Climate Change Risk Assessment will be undertaken in 2026, and a new NAP plan is then due in 2028.

The first NAP lays the foundations for a range of adaptation options, including managed retreat, but is light on details. Issues relating to managed retreat are complex, and involve consideration of how risks and costs associated with adaptation should be shared, what a managed retreat process should look like, whether people should be allowed to stay in areas when community services are withdrawn; as well as issues of equity, flood insurance, and managed retreat when climate change affects Māori coastal and river settlements.

Many of these issues remain unanswered by the NAP. It indicates that a hybrid approach using different adaptation options may be appropriate, and that the options used may change over time. It also indicates that councils should work with communities to assess options that will be adopted, but leaves key issues for future processes including further central government direction (including through RMA reform and local government review), the legislative mechanics of managed retreat (if required) and, more importantly, how such matters will be funded.

What is ‘managed retreat’?

Managed retreat is defined in the EDS paper as the process by which people and assets are moved out of harm’s way. There are only a few examples in New Zealand, and historically it has occurred through the voluntary acquisition of properties (largely at current market value, pre-disaster), such as the process of red-zoning areas after the 2011 Christchurch earthquakes which affected close to 8,000 properties, with more than 20,000 people being relocated. An ongoing example is the RiverLink Project in the Hutt Valley, which includes (as part of an integrated regeneration, flood protection and transport improvements project) provision for upgraded stopbanks and widening of the river to accommodate increased flood protection. This will involve the acquisition of 141 properties (with 112 already voluntarily acquired). Other examples, such as Matata, are both post-event and pre-emptive, with property damage having been sustained during an event in 2005, houses rebuilt and then a managed retreat process subsequently undertaken to remove people from an area subject to ongoing risk from debris flow.

The acquisition process involves the loss of land, buildings and infrastructure, both private and public, which is often not covered by insurance where there is no property damage. The escalation of climate change effects such as sea level rise and extreme storm events is likely to increase the need for managed retreat away from areas of harm.

Although this is a challenging process to navigate, the paper notes that international experience indicates managed retreat is still the most cost effective and often the only option available. Positive benefits include the reduction of risk and enhancement of community resilience.

Managed retreat can be contrasted with other retreat options including ‘unmanaged retreat’ which refers to the un-coordinated movement of people away from areas of risk, usually following a significant event (rather than being pre-emptive) or ‘transformational retreat’ which involves positive societal and environmental outcomes being actively sought as part of the managed retreat process.

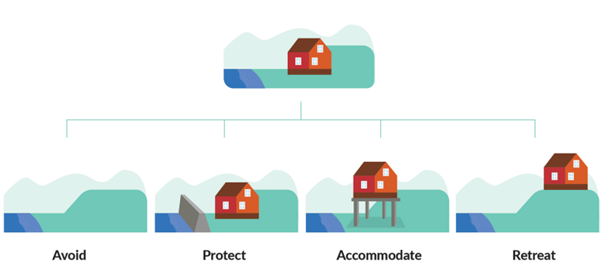

Managed retreat options are one subset of a range of adaptation options, which include responses such as risk avoidance (i.e. preventing future development in risk prone areas such as flood zones ); use of nature-based methods (e.g. natural flood management); or risk mitigation which accommodates flood/erosion events (e.g. raising floor levels etc) or use of hard protection structures (i.e. seawalls, stopbanks etc). The adaptation options were shown graphically in this figure from the NAP:

Principles identified by EDS as relevant to managed retreat

The EDS Paper poses the question ‘what should be the purpose(s) of managed retreat in Aoteoroa New Zealand?’ and identifies 21 relevant principles, a combination of which could form the basis for a managed retreat legal framework and related decision-making. It is worth reading the EDS paper for the full range of principles. We have included some examples below.

Transformative Principle - Social power and constraints should be transformed to deliver improved outcomes for people and nature

Remedial Responsibility Principle - People who need help should be given assistance

Least Advantaged Principle - It is important to protect the interests of those who are the least advantaged or have the greatest need

Intergenerational Equity Principle - Those currently alive have a moral obligation to protect the interests of future generations

Compensatory Justice Principle - Unjustified loss, damage or disruption should be compensated for

Comparative Justice Principle - Alike cases should be treated alike

Recognition Justice Principle - It is important to address the underlying causes of inequities

Te ao Māori Principles (Tino Rangatiratanga) - Māori should retain self-autonomy in decision-making over their land and resources

Ability to Pay Principle - Those who are wealthier have a greater duty to pay than those who are poorer

Polluter-pays Principle - Those responsible for causing harm should pay to remedy it

Subsidiarity Principle - Decisions should be made closest to those most affected by them

Procedural Justice Principle - People should have the right to participate in decisions that affect them

Voluntarism Principle - Voluntary action is to be preferred over compulsion

These principles differ significantly from the objectives and principles for managed retreat legislation released by MfE as part of its consultation on the (then draft) NAP. As noted by EDS , MfE’s objectives were relatively light on the specific outcomes sought by managed retreat, and are directed more at providing clarity around roles and responsibilities and process for managed retreat (including stronger tools for councils). The objectives and principles provided by MfE directly reference matters such as limiting the Crown’s fiscal exposure and reducing liabilities, including contingent liabilities, on the Crown; as well as ensuring risks and responsibilities are appropriately shared across parties including property owners, local government, central government, banks and insurance industries[2].

Funding Support

The availability of compensation is discussed as being a powerful incentive tool critical to the success of managed retreat. The Paper discusses reasons why public compensation for loss of residential property might be needed in New Zealand, some examples from overseas, and what a public compensation system in New Zealand could look like.

Twelve options are included in the paper, ranging from provision of full property replacement cost, creating a fixed compensation rate or cap, including for owner contributions; through to compensation based on the remaining habitable life of the property (with conversion from freehold to leasehold), and differentiations depending on knowledge of climate-related risk, whether the property is a principal place of residence or not, and the net worth and/or income of the property owner. The paper outlines the advantages and disadvantages (including likely palatability of the options and costs), and identifies particular options as worthy of further consideration.

The paper also addresses options for creating a public compensation fund, although the cost would be difficult to estimate. It briefly explores potential revenue sources, including increases in taxes or rates, additional home insurance or fossil fuel levies, new taxes (e.g. a comprehensive capital gains tax) or as part of the Climate Emergency Response Fund (through the Emissions Trading Scheme).

The paper also addresses the difficult questions of managed retreat of critical infrastructure (including potential costs and funding sources) and businesses, including horticultural, fisheries and tourism activities which have locational and/or operational constraints which impact their ability to relocate.

What happens from here?

Feedback is welcomed by EDS on the discussion questions, including which principles should be the basis for the managed retreat system, what compensation options (if any) should be available, and the sources. The full paper can be viewed here.

EDS’s intention is to provide two further working papers and a final synthesis report in December 2023, to inform the development of the Climate Adaptation Act, expected to be introduced to Parliament at the end of 2023.

If you have any questions about issues arising from the paper or climate change matters, please feel free to get in touch with our Climate Change and Sustainability team.

Latest Update: 20 Feb 2023

[1] https://www.cooneyleesmorgan.co.nz/Changing_climate_in_NZ

[2] Refer Figure 3 from MfE’s draft national adaptation plan document, reproduced at p16 EDS Report.